Dr. Bruce Burkett requests a suture.

His assistant hands him the curved, threaded needle and then pushes up Burkett’s glasses, which slipped down his nose as he leaned over to concentrate on a patient.

Bruce is trying to save a valuable Holstein dairy cow suffering from a rare, twisted stomach.

The successful surgery get the Holstein up and eating within minutes.

Bruce 52, grew up on a tobacco and corn farm and says he became a veterinarian because it would keep him in touch with agriculture.

“I don’t know what else I would do,” he says. “Since I was in middle school, this is what I wanted to do.”

Now in his 28th year as a veterinarian, Bruce maintains his passion for treating large animals, mostly cows and horses, even though that part of the practice dwindled. He used to do nothing else, but these days treating cows and horses accounts for about 15 percent of his business.

Bruce says his is the only independent veterinary practice in the county that does large-animal work. Many vets don’t do such work because “you can’t make a living” at it, Bruce says.

Many farmers have stopped hiring independent veterinarians like him to regularly check their cows.

Local Mennonite farmers mostly keep Bruce’s large-animal business going. The Mennonites often do regular herd checks during which Bruce assesses the herd’s health.

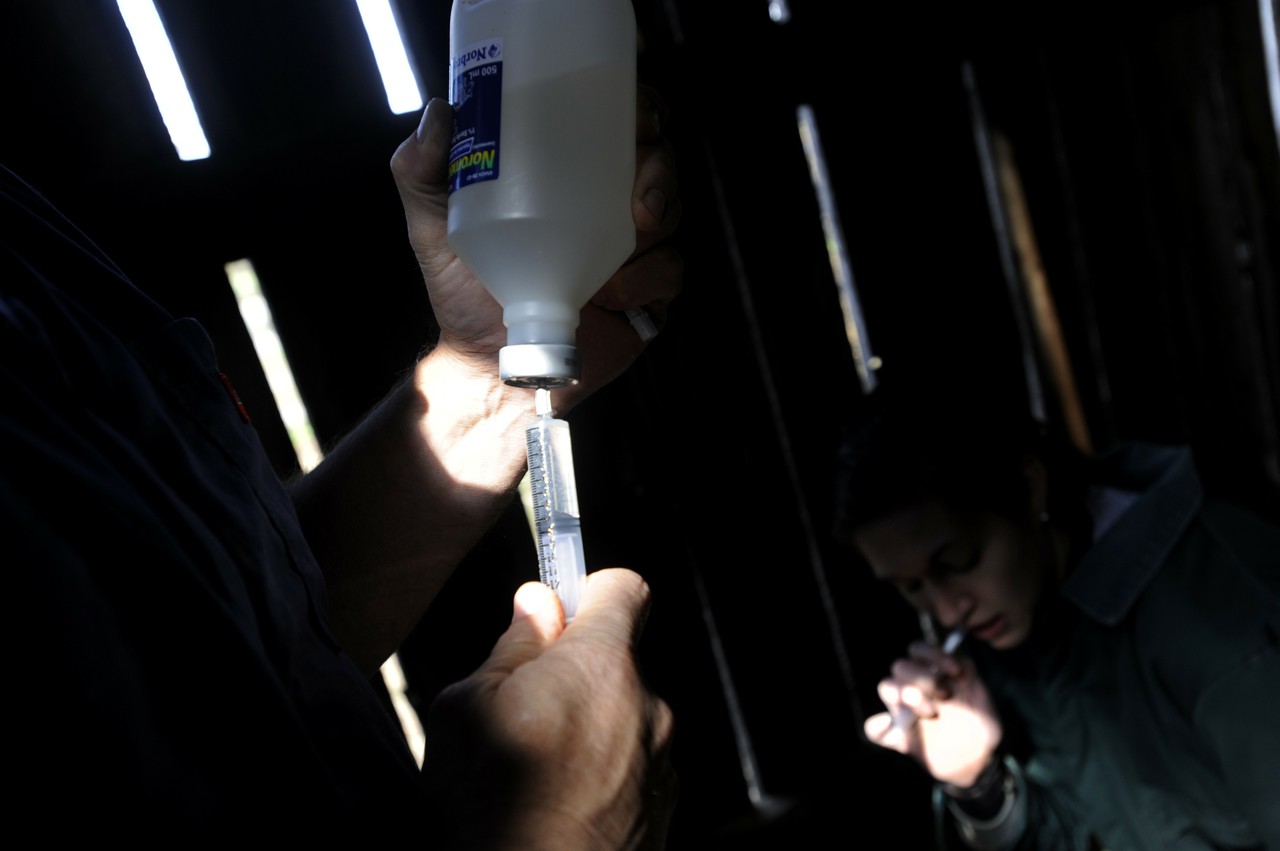

During such a check, farmer Mervin Weber asked Bruce to inspect a cow that stopped eating and begn losing her balance. Bruce put his ear to the cow and flicked her side a few times, then diagnosed the problem as a twisted stomach.

After surgery later that day, Alyssa Wilson, a licensed veterinary technician who works for Bruce, says she’d rather have him sew her up than a medical doctor.

“He takes more care and makes them look much better,” she says about Bruce’s suturing skill.

Wilson, one of 10 employees at Somerset Animal Hospital, often assists Bruce outside the office on large-animal calls.

Bruce’s wife, Pam, manages the office.

Bruce spends most of his days caring for cats and dogs, including spaying and neutering. He occasionally deals with an upset customer who bounced a check. He comforts the owners of family pets he couldn’t save.

Routinely, though, he hops in the car and heads out to a farm to check on someone’s cows.

It actually costs his practice money to care for large animals, he says. But Bruce keeps doing it because some farmers need the service.

“Business-wise it doesn’t make sense, but I enjoy it,” he says. “It’s a public service, so I’m going to keep doing it.”